|

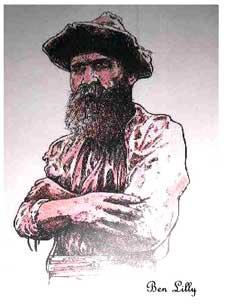

American Houndsman Ben Lilly

Ben Lilly and the Last of the Bears

By Dan C. Johnson

The great bear must have had some sense of the uniqueness of this approaching enemy. He must have learned something of man to live so long and grow so large feasting on his cattle. Past experience must have taught him he was pretty safe when he made the timber and could relax on the far side of the hill. But he hadn't lost this man in the timber, nor in the hills. For three days the man had hounded him through some of the roughest mountains in Arizona. And three times he had gotten close enough to put a rifle slug into his flank.

The great bear must have had some sense of the uniqueness of this approaching enemy. He must have learned something of man to live so long and grow so large feasting on his cattle. Past experience must have taught him he was pretty safe when he made the timber and could relax on the far side of the hill. But he hadn't lost this man in the timber, nor in the hills. For three days the man had hounded him through some of the roughest mountains in Arizona. And three times he had gotten close enough to put a rifle slug into his flank.

As the man and dog, bound together by a strand of rope and a common predatory instinct, struggled toward him through the waist-deep snow, the bear waited. No more running. Now he would fight. The gunshot wounds may have sapped some of his strength, but his rage would overcome that. He lay there in the thick brush, muscles tensed, fangs and claws poised to exact a fierce vengeance. He was 9 feet from the tip of his nose to the tip of his tail, and every ounce of his being was tuned to one purpose -- to kill.

Closer and closer came the objects of his hatred. Fifty yards. The dog, bawling and lunging against his leash, knew he was close. Thirty yards. His rifle poised, the man knew it, too. Twenty yards. That rippling crouch, like a cat before the pounce. Ten yards. The hated man's smell must have filled his nostrils and fed his rage. Five yards ...

"Anybody can kill a deer. It takes a man to kill a varmint."

The varmints Ben Lilly was talking about were mountain lions, wolves and, most especially, bears. Lilly had worked at a lot of different professions on his slow exodus to the west. Born in Alabama in the winter of 1856, he learned his father's blacksmith trade. Then he moved to Mississippi, Tennessee and Louisiana before shaking off the bounds of civilization. He worked as a farmer, a logger and a cowboy. But, mostly he hunted. That's what brought him west -- the search for new hunting grounds.

On this early spring day in 1913, he was working as a predator-control hunter, collecting bounties offered by individual ranchers and their organizations. He had pursued the large predators with a passion throughout his life, but now he was getting paid for it. He especially liked hunting grizzly. And three days ago he had struck the trail of a big one. He was dressed a little light for the chase, no coat, just a sweater for warmth. His only provisions were his rifle, his knife and a few matches. Nonetheless, he took to the trail and stuck to with a tenacity that made him a legend.

As was his custom, he had not eaten since striking the trail, pushing the bear each day from dawn 'til dusk, and huddling close to the hound and the fire by night. Now, the trail had brought him to a dense evergreen thicket where the sign and his instinct told him the bear was waiting. The rope that held the dog to him, and held him to the dog, was tied around his waist to leave his hands free for the rifle

He was floundering in the deep snow, and this may have saved him, because it hampered the bear's charge as it erupted from the thicket. Lilly's first shot to the chest slowed the animal in that small breath of time it took to take more careful aim and send a bullet just below the eye.

Bear, man and dog collided in a tangle of flesh and fur. The beast was down but not dead. Ben managed to work the muzzle of his rifle into the bear's chest and squeeze off a shot, but he could still hear a rasping breath. So he drew his knife and drove it into the grizzly's heart.

It wasn't the first bear to succumb to his blade. Southerners of his time carried knives as the Westerner would a six-gun. It was the weapon of choice for settling matters of honor and its use extended to the hunting fields. Lilly had learned the skill of knifemaking from his father and carried a large double-edged weapon of his own design. In the cane breaks of Louisiana, he had practiced the Southern sport of bear sticking, charging among the hounds to deliver an across-the-shoulder stab to the heart. The stab was made across the bruin's shoulder to the opposite side because animals tend to lash out in the direction of the pain, in this case, away from the hunter. Of course, sanity restricted this technique to black bears.

It wasn't the first bear to succumb to his blade. Southerners of his time carried knives as the Westerner would a six-gun. It was the weapon of choice for settling matters of honor and its use extended to the hunting fields. Lilly had learned the skill of knifemaking from his father and carried a large double-edged weapon of his own design. In the cane breaks of Louisiana, he had practiced the Southern sport of bear sticking, charging among the hounds to deliver an across-the-shoulder stab to the heart. The stab was made across the bruin's shoulder to the opposite side because animals tend to lash out in the direction of the pain, in this case, away from the hunter. Of course, sanity restricted this technique to black bears.

Despite his adherence to some traditions, Benjamin Vernon Lilly was an unconventional and complex man who set his own standards and stuck to them. He had the countenance of a Southern preacher but lived much of his life as a wild man -- preferring to sleep on the ground, or sometimes in a tree, to the comforts of hearth and home.

He married twice and fathered several children, but the allure of wild places tempted him from his domestic responsibilities. When he announced he was going hunting, he might not return for weeks or even months. Once when his wife asked him to shoot a chicken hawk that had been raiding their farm, Ben grabbed his rifle and took off after the bird. He returned, a little over a year later, and explained, "That hawk kept flying." To his credit, he did provide financially for his children throughout his life.

Theodore Roosevelt, whom Lilly had guided on a hunt in Louisiana, described him as a "religious fanatic." But an outdoor writer of the time summed the man up as "intelligent, using good language, fairly free of slang, entirely free of oaths; he touches no tobacco, uses no strong drink, not even coffee, and Sunday is said to be a hallowed day with him; the wildest animal is free to hudge him in camp on that day if he wants to, but is warned to leave no tracks for Monday . . . "

It was in Louisiana that Lilly's hunting prowess first brought him fame. Stories of his hunts reached Ned Hollister of the U.S. Biological Survey - later to become the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Lilly was commissioned to send in specimens for study and the Smithsonian museum in Washington still has mounts of ivory-billed woodpeckers, wolf, bear and other animals sent in by him.

The more time he spent in the wild, the more wild he became. In 1906, he signed all his property over to his wife and crossed into Texas, leaving all vestiges of domestic living behind. He had no money and only what provisions he carried. He sold bear meat and wild honey to buy what little he needed, and he continued to send specimens to Washington. His exodus continued across Texas and into Mexico, where he stayed for several years.

His exploits in Mexico are not as well documented as in the U.S.; nonetheless, he instilled himself into the lore of the region. There was, for example, the story of a large grizzly that claimed as his territory a favorite camping spot along the Camino Real, the famous trail that wound across western Chihuahua. The great bear, distinguished by a white star on it's chest, terrorized travelers for years along the trail and eluded all who attempted to kill it. Then the locales reported a bearded gringo passing through the area, and the bear was never seen again.

Lilly was 55 years old when he reentered the U.S. in southwest New Mexico, in 1911. He was about to turn his passion into a profession. The large predators plagued cattle ranchers in the southwest. One grizzly might kill $500 worth of cattle in a year, and that was a lot of money then. By 1914 the Federal government got into the act and began offering bounties.

With Federal and private bounties, plus the income from the specimens, he continued to send to Washington, Lilly was making a lot of money, but still lived the wild life and avoided the comforts of civilization. When he would arrive at a ranch that had solicited his services, bed and board was usually offered, but he would pitch camp nearby and sleep on the ground. He would stash supplies in caves throughout the region in order to avoid a trip to town. And would often pay people to deliver those supplies to him.

With Federal and private bounties, plus the income from the specimens, he continued to send to Washington, Lilly was making a lot of money, but still lived the wild life and avoided the comforts of civilization. When he would arrive at a ranch that had solicited his services, bed and board was usually offered, but he would pitch camp nearby and sleep on the ground. He would stash supplies in caves throughout the region in order to avoid a trip to town. And would often pay people to deliver those supplies to him.

His lifestyle contributed to his success. Where other hunters were constricted by home and obligations, Lilly moved with the freedom of his prey. Always seeking out new hunting grounds, he went were the quarry led him. In short, his home was wherever he happened to be at the time.

This mobility required that he travel light. His standard equipment consisted of a tin can for cooking, matches, an axe, the big Lilly knife for sticking and a smaller one for skinning, a blowing horn for calling the dogs and to serve as a drinking cup, dog chains, cartridges, and of course his rifle. He preferred the Winchester lever action, either a 30/30 for lions, wolves, deer and the like, or a .33 if he was after bear.

As for food, he only carried some dried corn or corn meal and a little sack of sugar. He seldom ate while trailing anyway and once the kill was made he would feast on whatever critter he had run to ground. He was particularly fond of mountain lion and believed, as did the Apache, that the well-muscled meat of the neck would convey the cat's strength and agility to the hunter.

More than any one man, probably more than any dozen men of his time, Ben Lilly contributed to the eradication of the grizzly from the southwest. He eliminated mountain lions and both species of bears from many of the large ranches. Some may consider these dubious accomplishments in light of today's environmental conscious. But one must admire his ability as a hunter and woodsman as well as his single-minded dedication to what he considered his calling.

Benjamin Vernon Lilly died on a "county farm" near Silver City, N.M., in December 1936. He lived the life of a true mountain man a half century after all his counterparts were dead. He was a unique character and an enduring legend of the Southwest.

To read his stories, pick up BEN LILLY'S TALES OF BEARS, LIONS AND HOUNDS

Return to Homepage

|

|